News │ Wednesday, 21 August 2013

Thinking, Fast and Slow

Lecture by Nobel prize laureate Daniel Kahneman at the Leopoldina

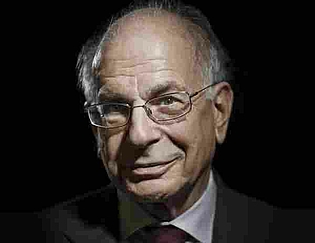

Image: Daniel Kahneman.

The Israeli-American psychologist Daniel Kahneman, born 1934 in Tel Aviv, was awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 2002. On Friday, 20 September, at 8 PM, he will give the evening lecture in the context of the Leopoldina Annual Assembly 2013 in Halle (Saale). He will be speaking about his book „Thinking, Fast and Slow“, identifying two modes of thought that influence human decision-making. System 1 can be identified with associative memory, and System 2 with the function of executive control.

Caroline Wichmann asked the Nobel prize laureate about the roles the two systems might play in science based policy advice and in communicating risks to the public:

Professor Kahneman, the German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina provides science-based policy advice. The scientific knowledge we prepare and make available should therefore offer politicians the most objective and rational basis possible for their decisions. Is this approach diametrically opposed to your System 1 thinking?

Science is defined by clear rules of objective, public evidence and logical inference. Conforming to these rules requires careful and deliberate reasoning of a kind that the more intuitive thinking that I associated with Type 1 (or System 1) processing is not capable of. However, intuitive and emotional thinking play an important part in both the passion and creativity of scientific research.

Professor Kahneman, scientific knowledge is subject to constant review and, as a matter of principle, can be refuted at any time. With regard to topics such as climate change or predicting volcanic eruptions, we have to identify and evaluate the issues, and communicate any associated risks. But does this stretch even your System 2 to its limits? And what role does System 1 then play?

It is important for scientists to realize that their ideal of knowledge that is based exclusively on objective evidence is not the only way by which people achieve the sense of subjective certainty that is associated with “knowing.” The subjective experience of certainty is associated with a state in which no alternatives to one’s beliefs are considered, and where the very possibility of ambiguity is denied. People can achieve subjective certainty with beliefs that they share with other people whom they trust and love. The certainty with which religious and political beliefs are held derives from this source, not from evidence, and the coherence of their belief is associative and emotional, not logical. Evidence has little hold on beliefs that are anchored in community norms. At least in the United States, the existence of man-caused climate change is perceived by the public as a matter of faith, not evidence. To achieve coordinated public action in that domain, it will be necessary to engage people’s intuitions and emotions – System 1 – and that change is unlikely to be achieved by evidence alone.