Topic in Focus

Pandemics as a Particular Challenge

Illustration: Sisters of Design

Vaccinating the population during a pandemic is a particular challenge. In order to prevent the further spread of a pathogen, action must be taken quickly. Newly developed vaccines can therefore be approved in an accelerated procedure. In this process, the risks of possible side effects caused by the vaccine are balanced against the acute health threats posed by the pathogen’s further spread.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, vaccines against the SARS-CoV-2 pathogen were developed faster than ever before. Scientists around the world worked on them using state-of-the-art technologies and governmental and supranational funding. In the process, they have been able to build on findings gathered about other coronaviruses. In December 2020, the first vaccine against COVID-19, the disease caused by SARS-CoV-2, was approved in the EU under accelerated procedures.

Workflows were also accelerated in this process: In a rolling review, the first data were already submitted to the European Medicines Agency for evaluation, while phase II and phase III studies were running in parallel. This meant that applications for approval of vaccines could be processed much faster than usual. This procedure thus saves valuable time without compromising on diligence. A vaccine only receives approval in Germany or the EU – even in an accelerated authorization – if it is proven to be of high quality, safety, and efficacy.

“Yes, we have an accelerated authorization in the case of the Covid 19 vaccines. It means that after the clinical trial was almost completed and it was clear that there was enough protection in the vaccinated group, i.e., a lot more people were protected there than in the control group, it was already started with the application for approval. This way, you lose the 6 months after the last vaccinated individuals. Because a study normally finishes 6 months after the last person has been vaccinated, provided that it was a 6-month study. Here a compromise was made in saying: it looks so good right from the beginning that we can already start the application for approval. And as a result, approval has been granted. We will see now, during the course of time, whether in the last vaccinated any irregularities still occur in the last few months regarding protection or side effects. And that looks relatively good. So this accelerated authorization, from my point of view, was completely justified in this particular situation.”

The accelerated authorization of the COVID-19 vaccines is a conditional authorization and is therefore subject to strict obligations. For example, manufacturers are required to continue to submit data showing that the benefits of the vaccine outweigh the risks. Apart from a conditional authorization, there is also an authorization under exceptional circumstances, which is colloquially referred to as an emergency approval. This is a special permission to use a non-approved vaccine under certain conditions in an emergency situation. In the assessment of the Paul Ehrlich Institute (PEI), this form of authorization is not an option for COVID-19 vaccines in Germany.

The example of HIV/AIDS demonstrates that it is not always possible to quickly develop an effective vaccine against a pandemic pathogen. Despite decades of research, there is still no vaccine against the virus. Nevertheless, drugs have been developed that enable infected patients to enjoy a comparatively long life.

“As the example of HIV shows: You can’t always produce a vaccine. With HIV, it was the drugs that turned this serious, deadly infection into a treatable disease that allows infected people to live to a normal age. If you had a vaccine today that was available worldwide and able to eradicate the virus worldwide, of course, that would be an even better situation than we have right now. But you would have to distribute that vaccine globally, and it would also have to protect in the long term if you want to eradicate a pandemic. That would be rather difficult.”

Prioritization – balancing ethics, law and medicine

If a vaccine is available, there is usually not enough for everyone in the beginning. Therefore, it must be determined which groups of people will be vaccinated first. This prioritization must be very well justified. Medical, legal and ethical considerations must be taken into account.

Several ethical principles play a role in such a decision: the self-determination of each individual, the prevention of serious harm (principle of nonmaleficence), justice and basic legal equality, solidarity, and urgency. All of these principles inform the decision and are linked to established virological and epidemiological evidence as well as the legal framework. During the coronavirus pandemic, in November 2020, the German Ethics Council, the Standing Committee on Vaccination, and the German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina published a joint position paper on the regulation of access to a COVID-19 vaccine, which also addresses the issue of prioritization.

“This is ultimately about the distribution of essentially important goods. Actually, if you want to formulate it very strongly, about life chances, but in any case about questions of life and health protection, which are of the utmost importance for all human beings and which therefore must be analyzed and also secured and justified not only medically, but also ethically and legally. Indeed, the principle of beneficence recedes somewhat into the background when it comes to individuals. The principle of beneficence is, so to speak, subject to the imperative to provide patients in medicine with the best possible care, i.e. ideally the optimal care. And that takes a back seat in a situation of scarcity that affects an entire society. Optimal care for individuals takes a back seat to, let’s say, the best possible care for as many people as possible who are particularly at risk. That’s when the principle of nonmaleficence comes into play. That means, in essence, the individual beneficence takes a back seat to a more socially driven beneficence.”

“This also coincides with the so-called common sense, such that if you ask people on the street: tell me, whom should we protect? Then they say: Well, those who are most endangered themselves, those who endanger themselves for the sake of others, and those who have vital roles in our society. Those are the three things. And those are exactly the three that we actually mentioned as well. And there have been surveys after our joint publication that show, that well over 90 percent of the respondents support this framework. So I believe it’s all sitting on a pretty good foundation.”

The constitutional principle to “treat equals equally and unequals unequally” is also applied when decisions have to be made about the distribution of scarce vaccines. For example, during the coronavirus pandemic, elderly people in nursing homes have a much higher risk of contracting COVID-19 with a severe course or a fatal outcome. This risk is several times lower for younger people living in their own homes. Therefore, unequal treatment – in this case, older people being vaccinated first – is justified. The question is similar when comparing nursing staff in clinics and home care by relatives.

“It is a very difficult question that I am asked frequently: What is actually the difference between the nurse on the ward and someone who cares for someone sick at home? Why aren’t they treated in exactly the same way? And the difference is that the nurse deals with many different patients, constantly changing, which poses a significantly higher risk compared to someone who always cares for the same person. And that, in turn, is different from someone in the general population who doesn’t do any of that. What is clearly stronger for these occupational groups is that they expose themselves to many special risks. And here, justice and solidarity and also the principle of nonmaleficence all go in the same direction – the principle of nonmaleficence because these people can also be multipliers at the same time, which means that they could potentially infect a large number of patients again.”

The prioritization for vaccination against COVID-19 cannot be applied to future pandemics, pathogens, and vaccines. While the ethical and legal principles remain the same, new pathogens may spread via different routes and lead to different disease courses. Thus, other risk groups could emerge. Prioritization must always be negotiated anew.

Vaccination as an individual decision and shared responsibility

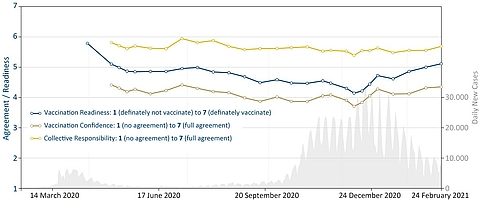

A number of reasons can be decisive in the individual decision for or against vaccination. In a pandemic, the perceived safety of the new vaccines plays a particularly important role. In the case of vaccination against COVID-19, it has been shown in the population that the greater the confidence in safety, the greater the willingness to vaccinate. Since the approval of the first COVID-19 vaccines, confidence in the vaccines’ safety has increased on average, which has also increased the willingness to vaccinate. Conversely, however, events that shake the confidence in vaccines’ safety can lead to a decline in the willingness to vaccinate.

Figure 6: Development of vaccination readiness, vaccination confidence and collective responsibility in Germany, statistical mean values throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Confidence and collective responsibility recorded according to 5C scale, short version (Betsch et al., 2018). Source: COSMO – COVID-19 Snapshot Monitoring, University of Erfurt, Germany | Illustration: Emde Grafik

The principle of community protection also plays a role in the individual decision to vaccinate. For example, people are more likely to be vaccinated if they know that vaccination will also protect chronically ill and vulnerable people in particular. Therefore, it is essential to have sufficient information on the extent a vaccination prevents not only the disease but also the transmission of a pathogen to other people. The aspect of community protection is also relevant for many people with regard to vaccination against COVID-19.

It is also crucial to reduce practical barriers in people’s s daily lives concerning vaccination. This is particularly true during the pandemic because people who have little confidence in vaccination are also more likely to be deterred by external circumstances. Surveys show that even organizing a vaccination appointment is perceived as a challenge by many people.

The World Health Organization (WHO) describes vaccination as both an individual right and a shared responsibility. During a pandemic, the responsibility for society and the healthcare system takes on added weight. The aim is to prevent the spread of the pandemic and, if possible, to establish herd protection. Even if a vaccine is such that it prevents the disease but not, or only to a limited extent, further infection, vaccination helps the community. Less severe illnesses reduce the overall burden of disease and relieves the health care system. This is particularly important during a pandemic.

During a pandemic, the state of knowledge is constantly changing. Researchers discover more about the pathogen, and they get to know its characteristics better and better. With new vaccines, actions against mutations and possible side effects are better understood over time. At the same time, the risk perception is shifting as a result of a pandemic. On the one hand, the population is particularly aware of risks of disease and infection. On the other hand, vaccines are new, and many questions arise. People like to make their decisions based on reliable knowledge and should be able to inform themselves about all aspects of vaccination – even during a pandemic.

“It’s simply a matter of taking questions seriously, addressing information deficits, picking people up where they are, and responding to their questions. For example, how could this all happen so quickly, and what about these new technologies? Should we be worried? Are there any severe side effects? Are there any adverse long-term effects that can occur? Just explain these things well. Explain in an evidence-based way. Explain it in an understandable way and take it seriously, and don’t sort of brush it off. These kinds of questions are totally justified.”

In order to provide everyone willing to be vaccinated with a supply of vaccine as quickly as possible, states may intervene more than usual in market mechanisms during a pandemic. The provision of a vaccine must not be based on supply and demand rules but must ensure prioritization, for example. In the EU, vaccines are purchased centrally for all member states and forwarded to the member countries. They ensure distribution within the country, organize logistics, set up vaccination centers, and ensure that every citizen has the opportunity to be vaccinated as quickly as possible.

“If there is an offer of vaccination available to all people, I think from an ethical perspective there is really little argument not to get vaccinated. Plus the burdens of vaccination are so low, whereas the burdens from the pandemic on individuals, on groups, but also on society as a whole are so high that I think there really is a moral obligation to do your part, so that we all get out of this together.”